A Story of Gentrification in San Francisco

To many longtime residents, gentrification here feels like losing not just apartments, but the cultures that made San Francisco feel like a cultural mecca in the first place.

By Marrion Cruz

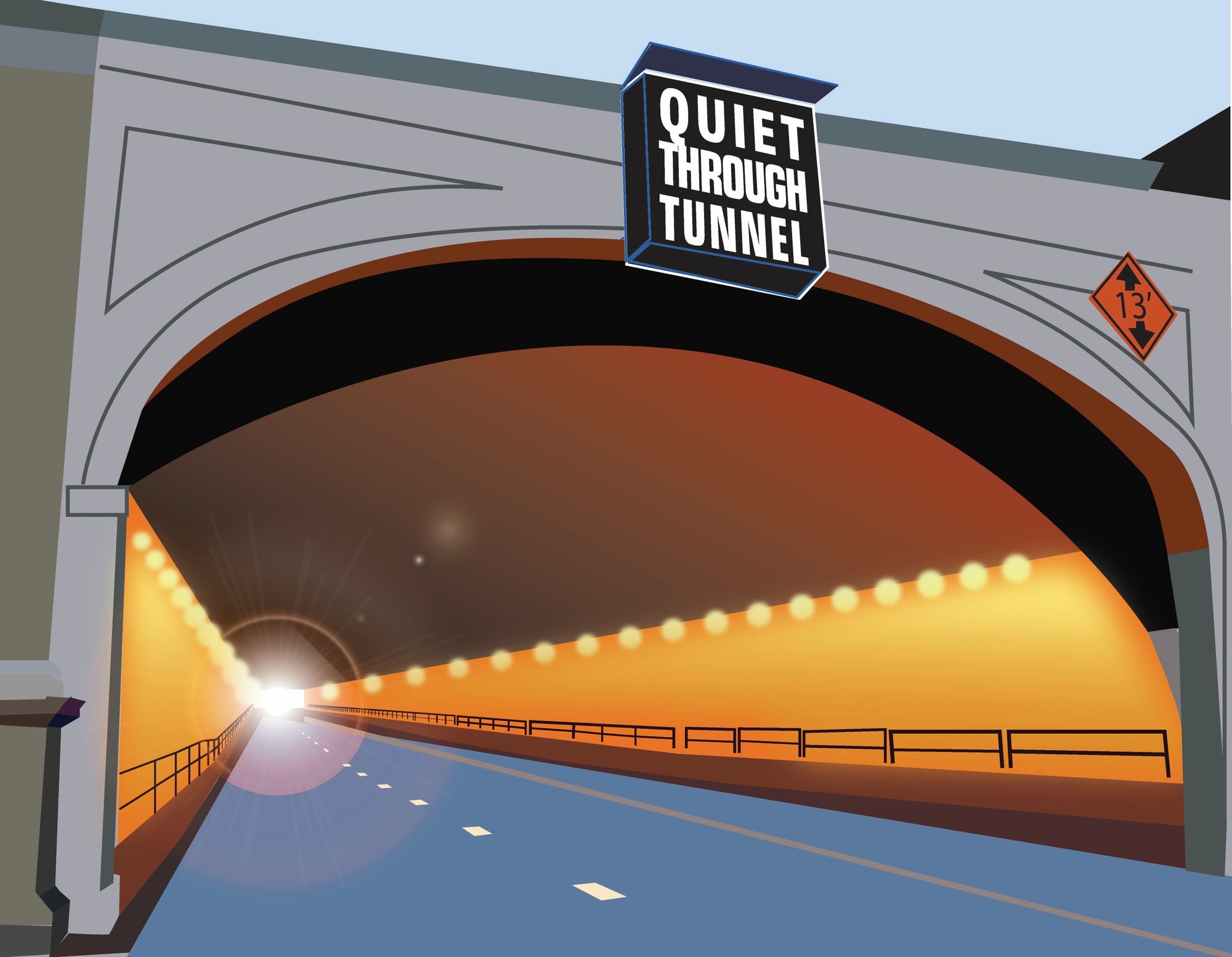

I grew up in a building whose front door opened straight onto Stockton Street, just shy of the tunnel at the seam of Chinatown and whatever was left of the city my parents recognized. They have been here for three decades; my grandparents, longer. From our narrow lobby, you could see the Ross on one side and the tunnel on the other, a loud mouth carved into the city.

The tunnel inhaled buses, transients, and grandparents walking grandchildren home from school on a daily basis. When I was little, I thought the white marble hotel above it was where the president lived. Later, I learned it was just for the rich and affluent. A neon-pink sign glared above the tunnel’s mouth: “QUITE THROUGH TUNNEL.”

I noticed the misspelling first, then the buzzing that never stopped, not even at 3 a.m., when the city shrank down to wind, and the high-pitched whine of street-cleaning trucks would grind up Bush Street. Already, a collision of old and new was the San Francisco I grew up in.

From the outside, it’s easy to flatten that movement into a simple story. In 2020, San Francisco was crowned as “the most gentrified U.S. city,” linking the Mission’s murals and Fillmore’s jazz clubs to a familiar set of villains: tech boom, luxury condos, rising rents. But researchers mapping neighborhood change in the Bay Area say the geography of that story is more uneven. A UC Berkeley/Urban Displacement Project map estimates that around 161,000 low-income households live in areas at risk of, or already gentrifying, but that close to three times as many census tracts are either already exclusive to higher-income residents or at risk of becoming that way.

Gentrification gets the headlines; long-standing patterns of exclusion quietly shape who gets to move into “good” neighborhoods at all.

My parents never left and are now getting ready to retire to the Philippines. They own land, a small lot, cars, and two houses in two cities. My mom shrugs and says, “We already made it back home”, when people ask whether she is worried about San Francisco’s future. That is one face of gentrification that rarely gets talked about: immigrants who arrived poor, squeezed into overcrowded housing and quietly turned wages from hotel and retail jobs into property back in the homeland, even as debate about “gentrifiers” swirled around them.

So when I walk along Mission Street in the Excelsior and see new storefronts between Silver and Ocean, I do not just see “gentrification.” I see another chapter in the same story: an older cafe where workers have gone for years before catching the bus across town, and a newer coffee shop down the street that hosted Sunday pop-ups during the pandemic, drawing lines for cinnamon rolls that sold out before noon. For the older shop, the pandemic meant its commuters vanished overnight. The regulars who used to come in at 6:30 a.m. were suddenly working from home, if they still had jobs at all.

It is tempting to cast one business as the villain and the other as the victim. But feminist geographer Leslie Kern has argued, in The Guardian and later in Fast Company, that coffee shops and boutiques are not the real culprits; closing them will not stop gentrification.

The deeper story is about who owns buildings, who can raise rents and who has the power to decide which communities are worth preserving. Gentrification, in this view, is what happens when land, housing and small businesses are forced to carry the weight of global inequality, immigration, student debt, tourism and the simple human desire for a better life, all at once.

Change is inevitable; justice is not. To many longtime residents, gentrification here feels like losing not just apartments, but the cultures that made San Francisco feel like a cultural mecca in the first place. When I step off the bus and walk through the tunnel with my son, I still look up at that neon sign telling everyone to “QUIET THROUGH TUNNEL,” a silent correction in its original thought. It's buzzing hums over the bus engines, now electric. The city, as usual, corrects itself while telling people to be quiet. Gentrification is loud. The people who have lived here the longest have every right to be louder.